Where Were You?

Case Exit

Most everyone in the USA over the age of 25 remembers what they were doing and where they were on Sept. 11, 2001, at 8:45 a.m. (New York City time).

Most of us also remember the first thoughts going through our heads.

I was stopped at a traffic light and caught the breaking news over the radio midsentence. Something about a plane crashing into a building. A freak accident? I glanced north toward downtown Salt Lake City (Utah). Nothing there to cause concern. I turned off the radio and continued my route. I parked the car and walked across the university campus to my destination. I remember an eerie quiet. The air felt heavy. Once inside the building—the student union—I noticed a small group gaping at an overhead TV set.

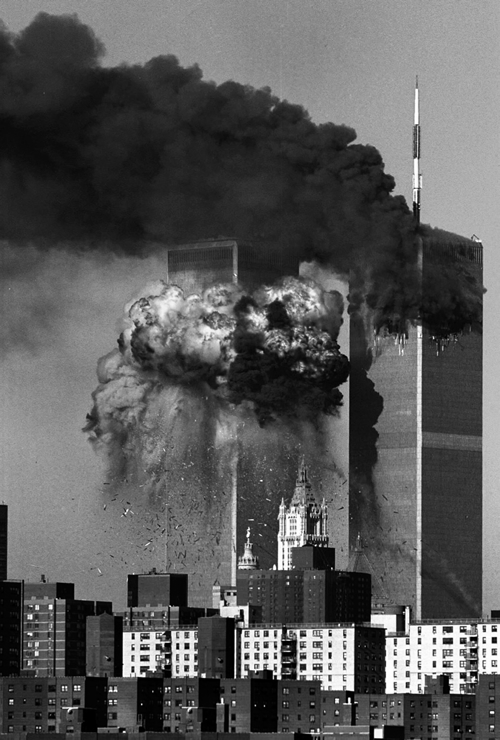

Televised scenes of billowing smoke and fire, the shadow of a photographer running with camera in hand, and replays of jetliners smashing into the World Trade Center in New York City (New York) told me—all of us—America was under attack.

I drove home and stayed close to our TV set, watching in disbelief, horror, and shock. Two 1,350-foot-tall buildings, the Twin Towers, collapsed. A third jetliner smashed into the west side of the Pentagon military headquarters in Arlington, Virginia. A fourth plane plunged into a vacant field in western Pennsylvania.

While I listened to the news in the safety of my home, the experiences of 911 emergency dispatchers could not be any more different. They swung into action.

Frederick County Emergency Communications Center Manager Micky Fyock remembers exactly what he was doing that morning when he first heard the news. “Our center has several TVs—one is always on the Weather Channel and the other is usually on CNN,” he said. “We noticed on CNN a fire in New York in one of their towers (World Trade Center), and of course this incident, for the fire-oriented personnel in the center, caught their attention. It didn’t take long before the real reason this building was burning revealed its ugly self. Then the second tower was hit, then the Pentagon, and rumors and reports of other places being hit started pouring in.”1

Fyock’s day did not end when the next 12-hour crew arrived. His next stop, as chief of the Woodsboro Volunteer Fire Company (Maryland), was traveling the 50 or so miles to the Pentagon to lend a truck and his expertise and that of four crew members to extinguish the fire still burning there.

The sight waiting for their help was unforgettable.

“We arrived at the Pentagon and saw firsthand what most people only saw on TV,” Fyock said. “I can tell you this, to see firsthand, to touch, and even smell the devastation and sights inside cannot be put into words.”2

More than 3,000 calls flooded the New York City Metro 911 system in the first 18 minutes (between the time the first and second towers were hit), and more than 57,000 calls came in during the 24 hours after the first plane hit the north tower. The calls from inside the towers totaled about 130, though many of those came from people in groups, sometimes of 100 or more. The New York Times covered the release of call tapes and transcripts from New York City Metro 911 on March 31, 2006:3

Repeat calls came from the 105th floor of the north tower, where 60 people had gathered, as well as other floors like the 97th and 83rd floors of the south tower.

Some dispatchers and supervisors now feel stricken by any suggestion that lives were lost because they relied on the traditional policy of "defend in place" firefighting, where only those at or above a fire in a high-rise building should move.

"When you listen to the tapes, it sounds like we are telling them the wrong thing and in reality we are telling them the right thing," said Judith Salgado, 36, a borough supervisor who worked in the Fire Department's Manhattan command center on Sept. 11. "No one thought those buildings were going to come down."

Audio recordings of emergency dispatchers trying to calm panicked civilians while juggling engine and ladder companies gave a glimpse into the despair on both sides of the phone. They listened to the voices of people, most of them heard for the last time. The New York Daily News wrote:4

Fire Department dispatcher John Lightsey still lives with the voices.

"Sometimes at night you hear stuff," he said. "You hear voices ... you know, calling for help."

Lightsey had the 7 a.m. shift at the FDNY's now-closed Manhattan Communications Center in Central Park. "It started like any other day," Lightsey recalled. "I handled a couple of EMS runs and some other pretty minor stuff."

"The phones never stopped," said Tyron Connell, a beginner from radio training, who estimated he spoke to "hundreds" of people.

One man called repeatedly from the north tower.

"The first time I spoke to him, he was relatively calm," Connell recalled. "By the fourth time, he was very distraught, talking about his kids and his wife. I think there was a point where he knew he wasn't going to get out. That is something I will never forget."

The attack reverberated across the country.

San Jose Fire Department ED-Q™ (retired) Deanna Mateo-Mih immediately drove to the communication center (San Jose, California). Crisis response plans were already in the works. The Emergency Operations Center (EOC) had been activated, and the fire stations were fortified against forced entry. Extra dispatchers were called in and waiting—just in case—with SJFD instructions for terrorist attacks.

“We didn’t know if the whole country was under attack,” Mateo-Mih said. “Nobody knew. Everyone was preparing for what might develop into war.”5

Fyock said Sept. 11, 2001, left a profound impact on his life. “We as dispatchers and we as citizens must always realize that at any moment our world can be turned upside down. But I am so proud that I chose this career. I am so proud of my brother and sister dispatchers all over the world. I truly believe we make this world safer.”6

Sources

1 Darata H. “Day Lives in Infamy. Dispatcher recounts tragedy that shook country.” Journal of Emergency Dispatch. March/April 2008. https://cdn.emergencydispatch.org/IAED-JOURNAL/Resources/2016/04/Journal_Mar-Apr08_Indexed.pdf (accessed Sept. 16, 2020).

2 See note 1.

3 Baker A, Glanz J. “For 911 Operators, Sept. 11 Went Beyond All Training.” New York Times. 2006; April 1. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/01/nyregion/for-911-operators-sept-11-went-beyond-all-training.html (accessed Sept. 16, 2020).

4 Kates B. “Desperate 9/11 cries still haunt FDNY dispatchers: ‘You hear voices ... calling for help.’” New York Daily News. 2011; Sept. 11. https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/desperate-9-11-cries-haunt-fdny-dispatchers-hear-voices-calling-article-1.957081 (accessed Sept. 15, 2020).

5 Fraizer A. “Slot on the Evening News.” Journal of Emergency Dispatch. 2017; Sept. 18. https://iaedjournal.org/6688-2/ (accessed Sept. 15, 2020).

6 See note 1.